How the Protestant Reformation Founded Lutheranism – and Changed the Face of World Religion

Image source: McNeillstown True Blues ILOL No. 46

Celebrating the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation and its Impact on Lutheran Religion and History

When you drive up and down the streets of your town, you’ll find churches of various denominations. The First Baptist Church on the corner; Second Presbyterian across from the grocery; the Lutheran Church downtown.

Your drive through town didn’t always look like that. Such diversity of religions and beliefs has been a relatively modern movement, one that began in 1517 with the Protestant Reformation, a shift that caused a massive exodus from the Roman Catholic Church – the overwhelmingly dominant form of Christianity and ruling force in Europe – and created an array of new religions, each with a set of beliefs and followers.

Until that point, for a person to feel connected to God, the Catholic Church was the only place to turn to hear the scripture or take part in the blessed sacraments from parish priests – baptism, confirmation, communion, penance, marriage, and last rites. And it was, the Church also claimed, through performing good deeds that led Christians to forgiveness of their sins and, upon death, to Heaven.

In addition to guiding souls to Heaven, the Pope and Church also had a far-reaching authority, ruling territory across Italy and, with the princes of the Holy Roman Empire, more than one-third of Europe. The Roman Catholic Church was the most powerful institution in the world.

This year marks the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation – a protest, a reform, and a significant turning point in world history. The Reformation had not only spiritual implications, but a far-reaching political impact.

Catholicism Corrupted?

There were numerous practices in Catholic dogma that, over the years, began to raise eyebrows from some followers. Over the centuries, corruption in the church was well-documented.

One such action called into question was the sale of indulgences, essentially slips of paper that guaranteed the recipient a spot in Heaven and lessened his or her time spent in Purgatory upon death. Akin to a Monopoly “Get out of Jail Free” card, a faithful Christian who had committed sin could earn indulgences if they performed a good deed, such as charity work. For centuries, indulgences could also be bought and sold.

The Pope in the early 14th century, Leo X, also offered indulgences to parishioners who helped to rebuild and finance St. Peter’s Basilica, the home of the Catholic Church in Rome that had fallen into disrepair. A preacher, Johann Tetzel, heavily promoted the sale of indulgences for this purpose, creating a marketplace for trips to Heaven.

Early Attempts to Reform

Image source: Faith Seeking Knowledge

There were early, failed attempts at reform. During the 12th century, John Wycliffe attacked corruption in the church, like the sale of indulgences, the concept of transubstantiation (that bread and wine consumed during the Eucharist is transformed into the body of Christ), and the low moral standards of priests, who often sold positions in the church and favored nepotism. Another rebel, John Huss, tried to lead a revolution – he was excommunicated, convicted of heresy, and burned at the stake.

Rewind to the late fourth century: St. Jerome translated the Bible into Latin (the official language of the Roman Empire). Yet in doing so, Concordia board member and Parliamentarian Rev. Harold Kamman recalls, there were small errors made in the translations – little inconsistencies that led to big misconceptions down the road.

For one, there was the theologian’s translation of the term “penance”. St. Jerome stated in his translation (known as the Vulgate) that, to gain forgiveness, one must do good and gain indulgences to get into Heaven – centuries later, critics would question that translation, stating that simply having faith and repenting sins, not doing good works, is enough to gain God’s grace.

Despite these inconsistencies, St. Jerome’s translation became the official text of the Roman Church’s Bible, its scriptures and the need to do good deeds relayed to millions of followers.

The Birth of the Lutheran Religion

Enter Martin Luther

The backstory of Martin Luther is almost one of fable: His ambitious father wanted his son to do good for himself and become a lawyer, so Luther enrolled in law school. One day, caught in a ferocious thunderstorm, Luther said a prayer to Saint Anna to save him – promising, if saved, to become a monk. The rains passed, he dropped out of the University of Erfurt, and went to live in an Augustinian monastery. Dad wasn’t happy.

One day, tucked away in the top of the monastery tower, Luther found a Bible. The moment became known as Luther’s Tower Experience; when he opened the book, he found scriptures that ran counter to the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. In particular, there was the line from Romans 1:17:

“For in the gospel the righteousness of God is revealed—a righteousness that is by faith from first to last, just as it is written: ‘The righteous will live by faith.”

It was that last line – “The righteous will live by faith.” – that became a turning point for Luther. He understood the passage to mean that to get to Heaven requires living only through faith alone – not by doing good deeds, such as building a church or earning indulgences.

“He learned that faith is reaching out to God and accepting what God has given us, which is his love and freedom,” Rev. Kamman says. “You don’t earn salvation; it’s already earned for you by Christ’s life and his dying on the cross as a way of paying for our sins.”

Luther developed, from the Tower experience, “Three Solas,” which outlined the three keys to salvation from sin and entry to Heaven.

- Sola Gratia (“by grace alone”): that one must rely only on God’s grace and salvation;

- Sola Scriptura (“by scripture alone”): that one must have access to the Bible and read and understand it for one’s own self; and,

- Sola Fide (“by faith alone”): that entry to Heaven and absolution of sin comes only through faith, not good deeds.

Luther was ordained as a priest and joined the faculty at the University of Wittenberg in Germany as a theology professor. There, he came to challenge portions of Catholic doctrine as well as St. Jerome’s Latin translations, particularly the use of the term “penance” and the effect those unfortunate translations had on Catholicism’s teachings.

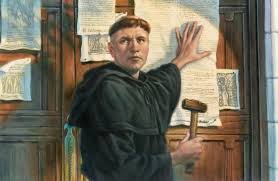

Lutheran History: Ninety-five Theses, Tacked to the Church Door

Image source: Middletown Bible Church

For Luther, it had become clear that the chief concern for the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church was economics and power, not saving souls.

In 1517, Luther published the famous Ninety-five Theses, a list that ran down his concerns with the Church doctrine. He tacked it to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg, a move that would spark the initial flames of the Protestant Reformation.

The core of Ninety-five Theses was that of the Three Solas – that the Bible was the central authority of religion, not the Church, and that people get to Heaven by grace and faith alone, not through doing good deeds. He condemned, in particular, the sale of indulgences as a way to earn a ticket to Heaven and he denounced the role of the Pope and priests, saying that the power to speak to God should be in the hands of all individuals, not just a select few. This was “the priesthood of all believers”, which would become a central tenet of Protestant doctrine.

Luther’s actions were not intent on ruining the Church, but rather, internal reforms and an end to certain practices. Yet, the Ninety-five Theses spread across Europe and was translated from Latin into German. Catholics began to rethink their beliefs and questioned the teachings of the Church. In Rome, it became evident that Luther was a threat to the Church and the Empire. He was accused of being a heretic and excommunicated by Leo X.

In 1521, Luther was summoned to the Diet of Worms in Germany to defend his actions and have his fate decided by Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. Luther refused to renounce his beliefs, was declared a heretic, and was banished from the Roman Empire. But before a decision could be reached on Luther’s fate, he fled and was seized by Prince Frederick, who hid the monk away in his castle.

The Role of the Printing Press in the Protestant Reformation

Image source: Haiku Deck

One of the key drivers of the Protestant Reformation was the development of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg during the previous century, circa 1440. The press was groundbreaking and through the use of metal movable type blocks, books and texts could be quickly created and broadly distributed.

There was no printing press in the time of Wycliffe, Huss, or other would-be reformers; the machine was a critical reason that Luther’s attempt at reform took root.

Luther spent 10 months of his exile at Frederick III’s Wartburg Castle, translating the Latin Bible, unreadable by most Europeans, into German. Gutenberg’s printing press allowed for mass production and distribution of the Bible and hundreds of thousands of copies of Luther’s translation spread throughout Western Europe and were translated into additional languages.

For the first time in history – without having to visit the parish priest – people were able to access scriptures in their own vernacular, without a massive expense and without having to step foot in a Catholic church and hear scripture from the mouths of clergy. (A side effect of the printed Bible was the spread of literacy throughout Europe.)

In their readings, people realized that a relationship with God didn’t require a bishop or the Pope, and that believers could all come to their own understanding of what the scriptures meant to the individual. Europeans began to challenge the Church’s teachings, sacraments, and concepts, such as transubstantiation.

With new interpretations of the Bible came new denominations of Christianity, an exodus from the Catholic faith and a contraction of the Church’s power. The waves of reform rolled through Europe and the Middle East.

From Germany to France and Scotland, to the Netherlands and Scandinavia, there was an explosion of various sects of Protestantism: the Lutheran religion, as well as Calvinism, Baptist, Methodist, and Anglican. And from those, even more denominations were created.

The Protestant Reformation Gets Political

The reforms swept up Europe, not only in a spiritual re-positioning, but a political upheaval, too. The Catholic Church had not only lost many of its faithful followers, but also much of its land.

Violence against the Church and its believers was widespread: religious zealots burned churches, palaces and libraries across Europe in revolt of Catholicism. Families were divided against one another. The Reformation led to a century of religious warfare, pitting Protestants against Catholics for control of Europe. Hundreds of thousands were killed, tortured and burned at the stake.

Religious art was also in the crosshairs: The Catholic Church had long idolized religious imagery through sculpture and paintings, and believed that art was a holy item. But Protestants pillaged Catholic churches, smashing and destroying an untold amount of imagery within it.

The Protestant Reformation offers Religious Freedom

Image source: Refo500

In 1545, Pope Paul III called together the Council of Trent, a multi-year meeting that produced a report that established reforms in the Catholic Church. The council ended, among other church practices, the sale of indulgences. Still, the council reaffirmed divisions between the beliefs of Catholics and Protestants and rejected the ideas of salvation through faith or scripture alone.

In Germany, the signing of the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 gave the power to each ruling prince, within the Holy Roman Empire, to pick the religion of their land – would we be Protestant or Catholic?

Decades later in France, Henry IV signed the Edict of Nantes, which established religious toleration and ended the religious wars between Roman Catholics and Protestants, which had left the country in near ruin.

Over the years, local European rulers, monarchies, and princes used the Protestant Reformation as opportunity to stop ceding authority to the Pope and take back control of their own lands and people. Over time, religious freedoms were granted to the individual.

Protestantism Comes to America

With the European settlements in the New World, Christianity spread to colonies of North America throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. The Anglicans of the Church of England settled in Virginia and the Pilgrims and Puritans had dissented from the Church of England and settled in New England. With the Virginia settlement holding church services in the English language, the early Lutheran settlers borrowed language from those gospels to hold their services in English, too.

The 1800s, in particular, saw a heavy emigration of Europeans to the newly declared republic of the United States. With that shift came an influx of new religions to America, many born from the Protestant Reformation.

Europeans brought with them diversity in religious freedom to the United States. When Rev. Kamman was a student in seminary in the late 1940s, “I was told there were 200 denominations in the United States,” the now 92-year-old recalls.

How Lutheranism Was Founded

The Lutherans organized in the U.S. as synods – a term translated literally as “walking together”. In 1847, his group organized as a Lutheran synod in Chicago, which today is The Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod.

Encouraged by his Lutheran family to become a pastor, Rev. Kamman graduated from Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri in June 1950 and was assigned to his first parish in Abilene, KS. The term Concordia is a central tenet of the Lutheran Church – its Book of Concord, published in 1580, includes ten “statements of Faith” that guide the religion’s followers. Concord is translated from Latin as “harmony” or “agreement”.

Rev. Kamman served five Oklahoma congregations over his 34-year career, including churches in the panhandle, in Boise City and Texhoma, at a time when the prairies were still recovering from the Dust Bowl. He retired in 1991 and has since served seven additional churches as a vacancy pastor. For a time, he worked as editor for the District News Section of the Missouri Synod’s Lutheran Witness newspaper. He’s been a resident of Concordia Life Care Community since our opening in May 2007.

And as for our Christian beliefs, it’s Luther’s initial solas, discovered high in that tower, that still ring true today for the religion’s followers.

“We recognize that we should trust in what Christ did to achieve salvation,” Rev. Kamman says. “It comes to us as a gift, and that means grace, and we cling to it and we accept it by reaching out with our hand, which means having faith. Salvation is not something you earn: Christ paid for it.”

Concordia Life Care Community will celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation in 2017 and the freedom for all to choose their faiths. At our independent living and continuing care retirement community, Concordia, we welcome and celebrate all religions and beliefs.